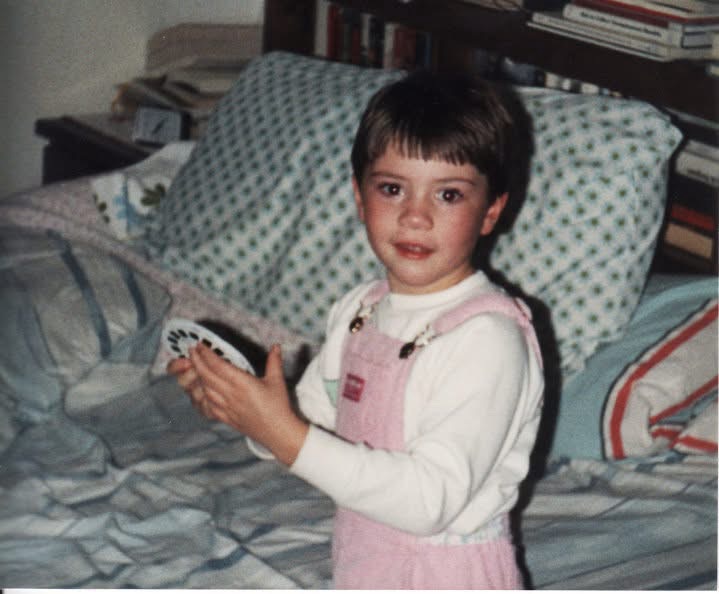

I grew up in what my mother called “working poor.” It wasn’t a label we wore publicly. It was just… life. At first, I thought we were like everyone else. I thought soup kitchens were just another kind of restaurant. I thought thrift stores were where everyone got their clothes. I thought rich meant your house had matching furniture and since I had never seen that, I assumed nobody had it.

Our house didn’t match. Not a single room. Not a single curtain rod. The tablecloths came from yard sales. The dishes were chipped. Our decorations were hand me downs, and none of them matched. We had buckets in almost every room to catch rainwater from the leaking roof. That roof collapsed again just before my mother died in 2021 and her kitchen flooded. I remember how heavy that made her heart, how tired she looked standing in the water.

My mom never made more than minimum wage in her entire life. She worked herself into the ground. She had three jobs. One in the school cafeteria. One as a caterer for teacher and district events — she served fancy lunches to people, some, who would later mock her behind closed doors. At night, she worked retail. She was yelled at. She cleaned up after others. She came home exhausted.

Still, she smiled at me.

Still, she made sure I ate.

My school supplies were bought on layaway, store brand and pieced together paycheck by paycheck. My school clothes came from Kmart, also on layaway. We couldn’t afford to buy them outright. In high school, my parents couldn’t afford the scientific calculator required for math class . I had to rent one from the school. I was embarrassed, but I didn’t say anything. I never did. That’s just what you do when you grow up working poor. You swallow the shame before it swallows you.

We decorated for every holiday but nothing matched. Our Christmas tree wasn’t a themed Pinterest masterpiece. It was a patchwork of joy and survival. Ornaments from the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s — some cracked, some glittered, all found in thrift stores. Our Thanksgiving centerpiece was a paper turkey my mom found at St. Vincent de Paul. I didn’t realize until recently that it was from the 1950s. We kept it for years and it was handed down to be after she died. I still put it up every Thanksgiving.

We didn’t go on vacation. Not once. Not a weekend away. My parents were married for decades and never took a single trip together. They couldn’t afford it. Every dollar was accounted for … bills, food, emergencies.

My mother was the kind of woman who hid school cafeteria leftovers in her coat so we could have dinner. She was so ashamed of it. She would slip food into her purse, walk out of that building with her head down, then come home and reheat it for us with love. She did this for years — from the time I was in middle school until I finished community college in 2007.

She endured harassment from teachers and some of her cafeterias colleagues who made fun of her for not traveling during school breaks. They laughed about how she “never went anywhere.” They made fun of her German accent. They called her a Nazi. She heard it all. She carried it. She died carrying it.

We ate at soup kitchens when I was little. I thought it was fun. It was a place where people smiled, where food came on big trays. I had no idea it was charity. My mom made it feel normal. She didn’t want me to see the struggle, but now I look back and I see it everywhere. In her shoes. In her cracked hands. In her silence.

My dad? He is the hardest working man I’ve ever known. He went into the Army at 16. Got his GED while serving. Afterward, he worked brutally physical jobs — warehouses and hauling freight. When I was in elementary school, he got his leg crushed in a conveyor belt. He drove himself to the hospital, nerves damaged, in searing pain. He couldn’t afford time off. He went back to work.

He injured his back, his wrists, his legs — again and again. And he kept working.

He became a long haul trucker for nearly 20 years. That meant he was gone for most of the year. I saw him maybe 18 days total annually. He was always moving. Always working. For us.

He’s in his 60s now. His body is broken. But he still works. Because he doesn’t know how to quit and he can’t afford to retire.

This is where I come from. This is who I am. This is who I will always be.

No matter how much money I make, no matter how many degrees I earn, no matter what rooms I’m invited into now, my heart will always beat in sync with the working class. With the blue collar heroes who wake up before dawn, who break their bodies for survival, who are mocked and overlooked but keep going.

I will never forget the smell of my mom’s coat, warm from the cafeteria, filled with our dinner. I will never forget my dad limping through the door, carrying the weight of his sacrifice. I will never forget how poor we were and how hard they worked so that I could dream of something more.

We were not lazy. We were not broken.

We were warriors.

We were the working poor.

And I will love us forever.

Leave a comment